Your cart is empty

Shop our productsIf you look at a globe and trace the rim of the Pacific Ocean, you'll notice something striking. A horseshoe-shaped belt stretching approximately 25,000 miles, dotted with volcanoes and earthquake zones, looping from South America up through North America, across the Aleutian Islands, down past Japan, the Philippines, and all the way to New Zealand. This is what is known as the Pacific Ring of Fire. And it is not just a catchy name. Around three-quarters of Earth's active volcanoes sit along this zone, and about nine out of ten significant seismic activities happen somewhere inside its reach. If you live in California, Chile, Indonesia, or even Alaska, you already live with it every day, whether you think about it or not.

Now, imagine a scenario. What if the Ring of Fire decided to rumble in a big way? Not just one volcano, but several at once. Not just a mild shake but something that made headlines around the world. People sometimes ask this half-seriously, like a doomsday movie pitch. But it's not a silly question. Volcanic chains do have patterns, and earthquakes along one stretch can sometimes trigger shifts further down. So what really happens if the volcanoes along the Ring of Fire erupt? Let's unpack it step by step.

What Is the Ring of Fire?

At its core, the Ring of Fire is a tectonic boundary system. Think of Earth's crust not as a solid, unbroken shell but as a jigsaw puzzle of plates that float on top of the molten mantle. Where those plates collide, slide under, or scrape past each other, energy builds up. In the Ring of Fire, most of that activity involves subduction zones—places where one oceanic plate dives under a continental plate. As that oceanic slab sinks, it melts, creating magma. That magma pushes up through cracks and faults, and sooner or later, it erupts as lava and ash.

That's why the Ring is so restless. From the Cascades in North America to the Andes in South America, from Japan's island arc to the volcanoes of the Philippines, the same process repeats. You get trenches in the ocean floor, like the Mariana Trench or Peru-Chile Trench, where plates bend down into the Earth. You get towering mountains and island arcs on the other side. And you get volcanoes that can sleep for centuries before waking with little warning.

So when someone asks what is the Ring of Fire, the plain answer is that it's the largest tectonic and volcanic belt on the planet, where Earth's plates are constantly in motion, colliding, and reshaping the surface.

How Was It Formed?

The Ring of Fire didn't appear overnight. It has been stitched together by millions of years of tectonic shifts. The Pacific Plate itself is huge, drifting westward and colliding with smaller neighbors. Along the eastern side, it pushes under the North American Plate and the South American Plate, creating mountain ranges like the Andes and the Cascades. To the west, it collides with the Eurasian Plate, the Philippine Sea Plate, and others, building arcs of islands and trenches.

Subduction is the main sculptor. When one plate dives beneath another, it doesn't just vanish. It melts, generates magma, and that magma finds weak points in the crust to rise up. Over time, volcanoes form. Some are violent stratovolcanoes like Mount Fuji, sharp and cone-shaped, built by repeated layers of lava and ash. Others are sprawling shield volcanoes with gentler slopes. Add earthquakes to the mix, because every time a plate jerks or slips, energy is released. That's why this part of the world shakes so often.

The result is not just dramatic scenery but an interconnected system of trenches, ridges, mountains, and fault lines. It is a reminder that Earth is alive and restless, always remaking itself.

Key Volcanoes and Seismic Zones

The Ring of Fire contains more than 450 volcanoes. Some names you've probably heard of, like Mount St. Helens in Washington, which blew its top in 1980. Or Popocatépetl in Mexico, often called "El Popo," which looms close enough to Mexico City to keep residents watchful. Or Mount Fuji in Japan, an iconic peak that is also classified as active, even if it last erupted in 1707 during the Edo period.

Other giants make news less often but pack a serious punch. Indonesia alone sits on dozens of active volcanoes. The Philippines has Mount Pinatubo, which in 1991 hurled so much ash into the sky that it cooled global temperatures for a couple of years. Chile, Peru, and Ecuador line up one fiery peak after another in the Andes.

As of 19 September 2025, according to the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program, roughly 44 volcanoes along the Ring are actively erupting. That does not mean they're all spewing catastrophic lava flows. Some just emit gas or small plumes. But it shows that the Ring is never quiet. Meanwhile, seismic hot spots like Japan, Alaska's Aleutian Islands, and Chile rack up hundreds of tremors each year, many too small for humans to feel, but all part of the system's constant adjustment.

Potential Impacts of Eruptions

Let's say a significant volcano erupts in the Ring of Fire. The immediate risks depend on the style of eruption. If it is explosive, pyroclastic flows—fast-moving avalanches of hot gas, ash, and rock—can sweep down slopes at speeds that outrun cars.

Volcanic eruptions are measured on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) from 0–8, where each level represents a tenfold increase in explosiveness—like the difference between a firecracker (VEI 2) and a nuclear blast in scale (VEI 6 or higher, as seen in Pinatubo). A VEI 5+ event can eject millions of cubic meters of ash, amplifying those local and global threats.

Lahars, which are volcanic mudflows triggered when ash mixes with rain or melted snow, can bury towns miles downstream. Ashfall can blanket regions, collapsing weak roofs, contaminating water supplies, and choking machinery.

Health impacts follow quickly. Ash particles irritate lungs, eyes, and skin. Aviation gets disrupted because volcanic ash clouds are dangerous to jet engines. Farmers lose crops as ash settles on fields. Livestock can die if water sources turn acidic or gritty.

Lava flows are slower but destructive. They bulldoze houses, roads, and anything in the way. Then there are the ocean-related risks. Undersea quakes or volcanic collapses can displace water and create tsunamis. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami wasn't from a volcano, but it was the same principle: sudden seafloor movement. If something similar happened along the Ring, millions of coastal residents would be in danger.

And on the global scale, a truly massive eruption could send enough ash and sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere to block sunlight. That creates what scientists call a "volcanic winter," where temperatures drop worldwide for months or years. Crops could fail, economies could stumble, and the ripple effects could reach far from the eruption site.

Historical Examples

History is the closest thing we've got to a test run of the "what if" scenarios. And the Ring of Fire has delivered plenty of lessons already. Take Japan in March of 2011. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast of Tōhoku. It lasted around six minutes, which is an eternity when the ground under you is rolling like a wave. People describe holding onto railings, watching buildings sway, and hearing everything groan. The quake alone was historic, but the tsunami that followed turned it into one of the costliest disasters on record. Entire towns were swept away. Nearly 20,000 people lost their lives. And then there was Fukushima, where seawater flooded backup generators and touched off a nuclear crisis. That chain of events showed the real nature of the Ring: it isn't just one hazard. It's multiple layers stacking together when conditions line up.

Fast-forward to 2025. A massive 8.8 quake rattled Kamchatka, that finger of land in Russia pointing down toward Japan. The epicenter was offshore, deep under the sea. Warnings for tsunamis went out across the Pacific, but this time, mercifully, damage on land was minimal because the region is remote and thinly populated. That's an important point. The Ring's energy is constant, but whether it turns into a global headline often depends on where it strikes. A big quake in a busy corridor like Tokyo or Santiago can mean billions in damage and tens of thousands displaced. The same quake in an isolated part of Alaska might make the news for a day and then fade, even though the energy release is just as staggering.

Other examples keep surfacing. Mount St. Helens in Washington State back in 1980 — that eruption literally blew the side off a mountain. People still tell stories about the sky turning dark, trees flattened like matchsticks, and ash drifting across the entire United States. Fifty-seven people died, but the lessons in monitoring and hazard mapping reshaped how volcanologists work. Then there's Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, 1991. That eruption pumped so much ash and sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere that average global temperatures dropped for a couple of years. Farmers in places thousands of miles away noticed shorter growing seasons and odd weather. That's a reminder that the Ring's reach doesn't stop at coastlines; it can bend climate patterns, even if only temporarily.

If you string these events together, you see a pattern of different scales of impact. Some disasters stay regional, devastating a valley or coastline but not changing the world. Others push far beyond their borders, cutting across industries, trade, and even global agriculture. When people ask "what happens if the Ring of Fire erupts," it isn't just about lava or shaking ground. It's about how one event can trigger many others. History shows the cascade is what makes it dangerous.

What If Multiple Volcanoes Erupt Simultaneously?

This is the doomsday-movie scenario that gets people talking. Could the Ring of Fire erupt all at once? Honestly, no. Each volcano is its own system with magma chambers, vents, plumbing, and triggers. They don't just talk to each other like dominoes lining up. But could several erupt in a short window of time? That's a different story. The Ring is long enough and restless enough that overlaps do happen.

Picture it. Say an eruption in Japan grounds flights across Asia. At the same time, a big Andean volcano disrupts agriculture in South America. Then throw in an undersea eruption that displaces water and sparks tsunami warnings. None of these would need to be linked directly. But to the outside world, it would feel like the Ring itself was waking up. Ash clouds could disrupt shipping and aviation on both sides of the Pacific. Ports might close for days or weeks. Crops could take hits from ashfall, forcing countries to scramble for imports. And if one of those eruptions was large enough — Pinatubo-scale or bigger — you could have genuine global cooling layered on top of everything else.

Still, scientists stress that while chain reactions sound cinematic, the mechanics don't really work that way. One eruption doesn't usually cause another thousands of miles away. The common thread is that all these volcanoes sit on the same tectonic belt, so when activity is high in one area, it reminds us that the rest are capable too. In other words, unlikely doesn't mean impossible. Nature has a way of humbling our sense of certainty.

Preparation and Survival Tips

This is the part that matters if you live anywhere near the Ring, which, statistically, is hundreds of millions of people. Preparation isn't about paranoia; it's about being ready for when things inevitably rumble. Agencies like the USGS in the United States or the Japan Meteorological Agency track seismic and volcanic activity constantly. Their alerts are worth paying attention to, even if they sometimes feel routine.

Modern volcano monitoring uses seismographs to detect underground rumbles, GPS sensors for ground swelling, gas analyzers to sniff out rising magma, and satellite imagery to spot heat anomalies from space. These tools can give days or weeks of warning for eruptions, turning what used to be surprises into manageable events.

Every household in a risk zone should have a kit. Not a "maybe someday" plan but an actual box in the closet. Water for at least three days. Shelf-stable food. Flashlights. Batteries. A hand-crank or battery-powered radio. First aid supplies. Copies of documents sealed in plastic. Sturdy shoes, gloves, and dust masks if you live in an ash-prone region. These are small investments that buy time when roads are blocked or stores are closed.

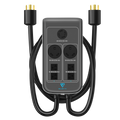

Power outages are almost guaranteed after big events. Earthquakes knock out substations. Ash takes down power lines. If you want peace of mind, portable power is worth considering. Something like the Elite 100 V2 portable power station can keep phones charged and lights running for a couple of days. If you're responsible for a household and need more, the Apex 300 home backup power can cover a refrigerator, internet router, or even medical devices until the grid comes back.

Community matters too. Knowing your neighbors, sharing resources, and being familiar with local evacuation routes make survival more than just an individual exercise. When Mount St. Helens erupted, it wasn't just officials who helped people; locals pulled each other out of dangerous spots. The same goes for quakes — the first hands pulling survivors from rubble are often neighbors, not rescuers flown in later.

Conclusion

The Ring of Fire will keep moving whether or not we're paying attention. That's what Earth does. Volcanoes erupt, earthquakes shake, tsunamis cross oceans. Sometimes the results are local, sometimes they ripple outward and touch everyone. The question isn't "will it happen" but "when" and "how ready will we be."

Preparedness isn't glamorous. It's not an action movie finale. It's water jugs in a closet, batteries in a drawer, a power station tucked under a desk. It's boring until the day it isn't. And then it feels like the smartest move you ever made.

The Elite 100 V2 portable power station and the Apex 300 home backup power are two examples of tools that fit this philosophy. They don't prevent ash from falling or waves from rising, but they make daily life bearable when infrastructure takes a hit. And that's really what living near the Ring of Fire is about — not pretending it won't erupt, but making sure you're ready when it does.

Shop products from this article

Be the First to Know

You May Also Like

Why Is California So Hot? Understanding the Heat

Axial Seamount Eruption 2025: What Really Happens If This Volcano Blows